The Pediatric Cost of Atmospheric Intervention and Environmental Uncertainty

Executive Summary

Children are uniquely vulnerable to environmental exposures during pregnancy, infancy, and early childhood. While air pollution and toxic exposures are well-established pediatric health risks, new and poorly regulated atmospheric manipulations raise additional alarms that demand scientific transparency and ethical scrutiny.

Key points:

- The developing fetus and newborn are biologically vulnerable to airborne toxicants due to immature detoxification systems and high respiratory rates.

- Established science links particulate air pollution to adverse birth outcomes, respiratory disease, and neurodevelopmental harm.

- Geoengineering and atmospheric modification introduce additional stressors into an already overtaxed environmental system via the atmospheric injection of nano-aerosol toxic metals.

- In pediatrics, uncertainty itself is a risk factor when exposures are involuntary and intergenerational.

- Children deserve the precautionary principle, rigorous oversight, and informed public discourse.

The First Breath Matters: Pediatric Foundations of Environmental Vulnerability

From the moment a child takes their first breath, they become intertwined with their environment. Newborns inhale more air per kilogram of body weight than adults, while their lungs, immune systems, blood–brain barrier, and detoxification pathways are immature. This makes early life exquisitely sensitive to airborne exposures.

Decades of pediatric and environmental health research demonstrate that prenatal and early postnatal exposure to air pollutants including fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅), nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and toxic metals is associated with increased risks of:

- Preterm birth and low birth weight

- Infant respiratory distress and wheezing

- Childhood asthma

- Neurodevelopmental delays and behavioral disorders

These are not speculative harms. They are well documented across large epidemiologic studies and form the foundation of modern pediatric environmental health.

What We Know: Established Environmental Health Science

Air pollution is one of the most extensively studied environmental threats to children worldwide. Major health organizations recognize it as a leading contributor to pediatric morbidity and mortality.

Fine and ultra-fine particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, cross the placental barrier, and enter systemic circulation. Studies demonstrate that prenatal exposure to particulate matter is associated with altered immune development, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signaling in the fetus and are biological mechanisms that may predispose children to chronic disease later in life.

Importantly, these harms occur even at levels considered “acceptable” by regulatory standards, implying that current thresholds may not adequately protect developing children.

From a pediatric standpoint, this body of evidence establishes a clear baseline: the atmosphere is not a neutral background. It is a delivery system.

Emerging Concerns: Atmospheric Modification and Geoengineering

Against this backdrop of known vulnerability, proposals and activities involving atmospheric modification now being often grouped under the term geoengineering warrant careful examination via the pediatric lens.

Geoengineering refers to large-scale technological interventions intended to alter atmospheric or climatic processes. These include solar radiation, aerosol dispersal, and other methods designed to influence temperature, cloud formation, or weather patterns. (See the New MDS, Episode 36.)

While proponents frame such approaches as ‘climate mitigation tools’, there is limited understanding of their downstream biological and ecological effects, particularly on vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, infants, and children.

From a pediatric perspective, several concerns emerge:

- Lack of long-term toxicological data on materials proposed for atmospheric dispersal

- Absence of pediatric-specific risk assessment

- Limited transparency, oversight, and public consent

- Potential for cumulative exposure in combination with existing pollutants

What is missing is the capacity to distinguish between documented environmental harms and emerging or contested claims regarding geoengineering practices. However, in pediatric medicine, a lack of certainty does not equal lack of risk.

Why Uncertainty Is Not Neutral in Pediatrics

In pediatric medicine, we apply a different ethical lens than in adult risk modeling. Children cannot consent. They cannot opt out. And they will live longest with the consequences of today’s decisions.

Historically, many pediatric health crises (consider lead exposure, tobacco smoke, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, etc.), were recognized only after widespread harm occurred. In each case, early warnings were minimized due to incomplete data, economic interests/influences, or regulatory inertia.

The lesson is clear: waiting for definitive proof can itself cause harm when exposures are population-wide and involuntary.

When atmospheric interventions are deployed without any pediatric risk consideration we repeat a familiar pattern which we’ve seen with everything from the irretrievable alteration of our food supply with GMOs/pesticides as well as the introduction of mRNA technology: experimenting first and studying outcomes later, often on children.

Intergenerational Ethics and Epigenetics:

Who Bears the Risk?

Environmental decisions made today shape the health of future generations. The fetus developing in utero is already responding epigenetically to maternal exposures, nutritional status, stress, and environmental toxicants.

If atmospheric conditions are altered whether deliberately or inadvertently such changes may influence immune programming, neurodevelopment, and lifelong disease susceptibility, with identification of root causes difficult, if not impossible, to later identify.

From an ethical standpoint, this raises fundamental questions:

- Who decides acceptable risk for children not yet born?

- What level of evidence should be required before large-scale environmental interventions proceed?

- How do we ensure transparency, accountability, and independent oversight?

Pediatrics demands that these questions be asked before, not after, widespread exposure.

Educate to Regenerate: A Pediatric Call to Action

At GMOScience, our mission is not limited to genetically modified organisms. It extends to the greater environmental systems that shape human health; soil, food, water, and air.

Since our founding in 2014, GMOScience has worked to challenge prevailing assumptions about the safety of genetically modified organisms and their associated pesticides, while expanding public and scientific understanding of the health and environmental consequences of genetic manipulation of the natural world.

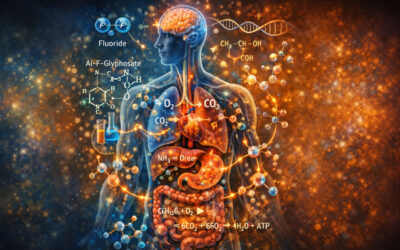

A Pediatric Bill of Rights for a Healthy Atmosphere

As a complement to the scientific and ethical issues raised in this article, GMOScience has proposed in the past a Global Children’s Health Bill of Rights — modeled after our own US Constitution designed to enshrine fundamental protections for children’s environmental health.

As a complement to the scientific and ethical issues raised in this article, GMOScience has proposed in the past a Global Children’s Health Bill of Rights — modeled after our own US Constitution designed to enshrine fundamental protections for children’s environmental health.

This Bill of Rights legalizes the foundational responsibility of a moral society; that children have the right to clean air, water, and food free from unnecessary toxic exposures, and asserts that public policy must prioritize the protection of developing bodies and brains from involuntary and unnecessary environmental insults.

It calls for transparency, accountability, and precaution in environmental decision-making, particularly where rapidly emerging and unstudied technologies or large-scale interventions (including atmospheric modification) introduce new risks to vulnerable populations.

By grounding environmental health policy in the rights of the child, the Bill provides a moral and legal lens through which to evaluate practices that alter the air our youngest breathe and the ecosystems that sustain them.

To educate to regenerate means:

- Educating parents, clinicians, and policymakers about established environmental health risks

- Regenerating trust through transparency, rigorous science, and ethical responsibility

- Applying the precautionary principle when children’s health is at stake

This is not an argument against innovation or climate solutions. It is an argument for pediatric-centered science, informed consent, and humility in the face of biological complexity. To proceed without considering our children’s well-being is not only unmitigated arrogance, but unconscionable.

Children deserve clean air, honest science, and a future shaped by care rather than convenience.

References

- World Health Organization. Air pollution and child health: prescribing clean air.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Ambient Air Pollution: Health Hazards to Children.

- Perera FP et al. Prenatal air pollution exposure and child neurodevelopment. Environmental Health Perspectives.

- Trasande L et al. Early-life environmental exposures and chronic disease.

- Danger in the Air: How air pollution affects children.

NOTE: For more expansive reading on relevant topics in children’s health, please visit my substack.