How genetically engineered and synthetic biology–derived proteins may quietly shape immune health and gene expression.

Modern food and biotechnology are increasingly built on a simple promise: if a protein looks the same on paper, it should behave the same in the body. This assumption underlies many genetically engineered and synthetic biology–derived foods now entering the marketplace, from precision-fermented dairy proteins to lab-produced amino acids and enzymes.

But human biology does not operate on paper.

The immune system, in particular, is not designed to evaluate chemical formulas or regulatory definitions. It responds to structure, pattern, and familiarity. When proteins are made in new ways, even subtle differences can matter, especially for children, whose immune and metabolic systems are still developing.

This article explains, in plain language, why “highly similar” proteins are not always biologically identical, how immune signaling can influence epigenetics (gene expression), why synthetic biology is accelerating this issue, and what precautionary solutions are available.

What the Immune System Actually Recognizes

When we eat a protein, our immune system does not assess the entire molecule at once. Instead, it encounters small surface regions (like tiny identification tags) on that protein. These regions are known in immunology as epitopes, but they can be understood simply as recognition points.

If these recognition points match what the immune system has seen before, tolerance is maintained. If they differ even slightly, the immune system may respond. This response does not need to look like a classic allergy. It can be subtle, delayed, or cumulative, showing up as low-grade inflammation, digestive symptoms, immune imbalance, or metabolic stress.

Importantly, very small changes in protein folding or attached sugar molecules can create new recognition signals, even when the protein’s basic function appears unchanged.

Why Production Method Matters

Traditionally, food proteins came from whole foods: milk from cows, eggs from chickens, and legumes from plants. These proteins entered the human diet alongside complex food matrices and through long evolutionary exposure.

Today, many proteins are produced using genetically engineered microbes through processes such as precision fermentation. In these systems, bacteria, yeast, or fungi are reprogrammed to manufacture large quantities of a target protein.

While the final protein may share the same amino-acid sequence as a naturally occurring one, the manufacturing environment matters. Proteins made in non-native systems can differ in how they fold, how sugars are attached to them, and what trace byproducts accompany them. These differences are often invisible to standard safety assessments but remain biologically relevant.

To regulators, the protein may be considered “substantially equivalent.”

To the immune system, it may appear new.

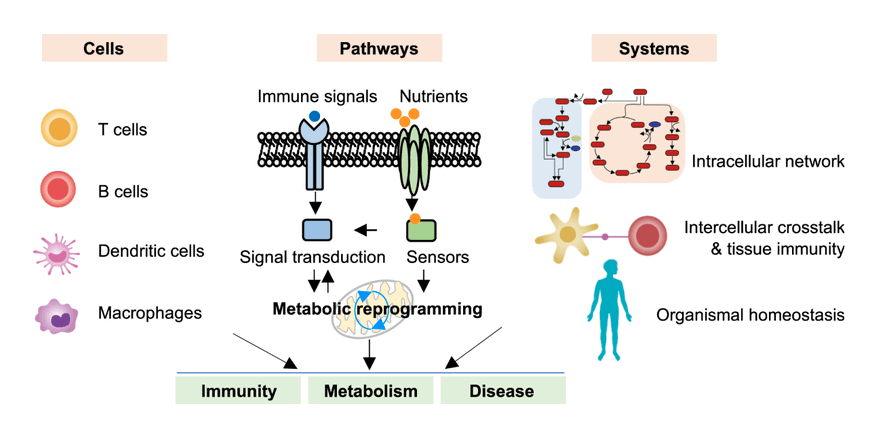

Immune Signaling and Epigenetics: How Small Signals Become Lasting Changes

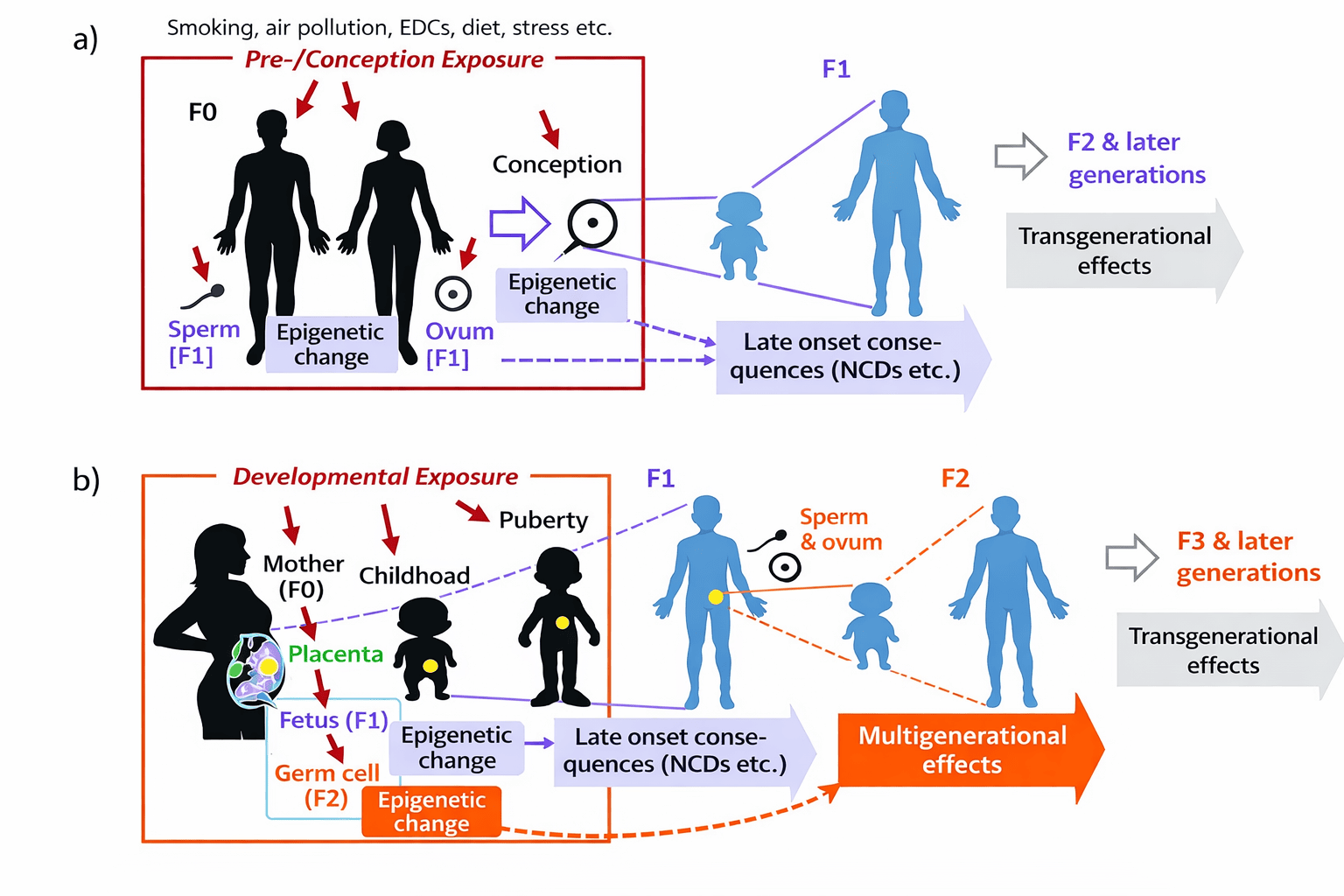

When the immune system encounters something unfamiliar, it communicates using chemical messengers such as cytokines. These signals do more than trigger short-term responses. They can influence epigenetics: the system that determines which genes are turned on or off.

Epigenetics does not change DNA itself. Instead, it alters how tightly genes are packaged and how actively they are expressed. These changes are responsive to environmental inputs, including inflammation, metabolic stress, and immune activation.

Repeated low-grade immune activation, particularly during early life, can result in lasting shifts in gene expression. This is now well established in immune and metabolic research. The concern is not immediate toxicity, but long-term programming.

Why Children Are Especially Vulnerable

Children are not simply mini adults. Their immune systems are learning what to tolerate. Their metabolic pathways are calibrating energy use. Their brains and immune systems are in constant communication.

During infancy, early childhood, and puberty, epigenetic systems are particularly sensitive. Signals received during these windows can shape lifelong patterns related to allergy risk, autoimmunity, inflammation, and metabolic disease.

This means that absence of short-term harm does not equal safety, especially when exposures are repeated and widespread.

The Role of Glycosylation and Metabolic Signaling

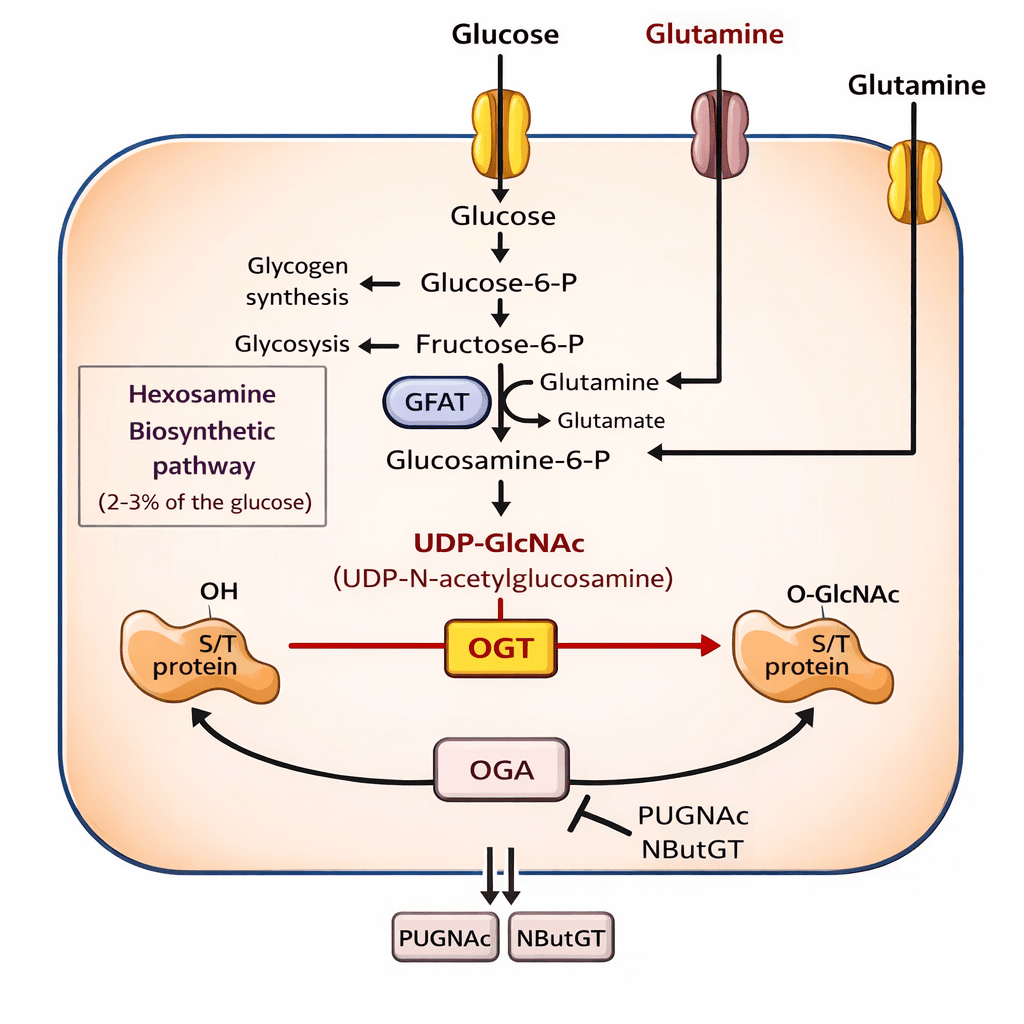

Another layer of complexity comes from glycosylation defined as the sugars attached to proteins. These sugar patterns influence how proteins interact with immune receptors and how cells interpret nutrient abundance.

High exposure to refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods increases metabolic signaling pathways that modify proteins inside cells. These modifications can alter insulin signaling, immune responses, and gene expression.

When novel proteins are introduced into this already stressed metabolic environment, the effects may be amplified rather than isolated.

Why Synthetic Biology Is Accelerating the Issue

Synthetic biology is rapidly expanding the number of novel proteins in the food supply. These include animal-free dairy proteins (think Bored Cow®), fermentation-derived amino acids (e.g., L-tryptophan), enzymes (proteases for tenderization, lipases for flavor in cheese, and amylases for starch modification), and additives (vitamins, prebiotics, ‘natural coloring’).

Most of these products enter the market without long-term human studies, pediatric trials, or evaluation of immune or epigenetic outcomes. Regulatory frameworks were designed to detect acute toxicity—not subtle immune or gene-expression effects that emerge over years.

This creates a growing regulatory blind spot between technological capability and biological understanding.

Just for the record, there are no human clinical trials on animal-free daily product in the scientific literature which reflects the novelty of the technology and lack of regulatory safety assessments.

Practical, Precautionary Solutions

This issue does not require fear or rejection of all technology. It requires discernment and precaution, especially where children are concerned.

Whole foods with long histories of human consumption provide proteins the immune system recognizes. Minimizing reliance on ultra-processed and novel protein isolates reduces unnecessary immune signaling. Supporting gut health, dietary diversity, and metabolic resilience helps buffer immune responses overall.

Equally important is asking better questions about long-term safety, transparency in production methods, and the need for child-specific research before widespread adoption.

A Closing Thought

Biology is not binary. Safety is not proven by sameness on paper. The immune system responds to nuance, pattern, and context.

As genetic engineering and synthetic biology reshape the food supply, we must ensure that innovation does not outpace precaution, especially for the youngest and most vulnerable among us.

Children deserve food systems that support their long-term health and not assumptions that overlook how biology truly works.

References

- Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature.

- Zhang Q et al. Protein glycosylation in immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol.

- Feinberg AP. Epigenetics at the epicenter of modern medicine. JAMA.

- Godfrey KM et al. Developmental origins of metabolic disease. Am J Clin Nutr.

- Varki A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology.

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature.

- Smith PM et al. Gut microbiota metabolites and epigenetic regulation. Science.